The 23 Most Influential Comic Books of All Time

Spoiler: This is a list of the 23 most influential comics of all time. NOT the best. NOT the most popular. In fact, there will be some you have never heard of. But I guarantee you have felt the influence later on.

The influence of comic books can be felt across many aspects of society. It can be groundbreaking, showing us something fresh and new. It can be disruptive, pushing the boundaries on what we think we can manage in visual literature. It can also be reflective, forging the commentary on where we are now and where we hope to be in the future. From political influence to sex education and cultural identity, there’s a whole lot of thanks owing to comic books and their creators. As revelatory as this might be, the struggle continues to be very real in convincing others of the power of comic books. Which leads to the question of where to start. There are so many great comics to read, you may need a little help discerning the best ones to start with. That’s where this list comes into play.

Again, you may not like every book on the list, and that’s okay. This is a list of the 23 most influential comics of all time. It is an opportunity to see the path they forged into future reading. Without these comic books, our reading lives may have been very different today.

The First of the First Influential Comics Books

The First Ever Comic Book

As long as there has been art, there have been comics. Cartoons existed as early as the Middle Ages, usually as a prep before creating the main piece of art. Manga made its debut on emakimono (scrolls) as early as the 12th century. If we’re going to split hairs, the first published and acknowledged comic book was Vieux Bois by Rodolphe Töpffer (also known as The Adventures of Mr Obadiah Oldbuck). It was first published in Geneva (Switzerland) in 1837 and predates the more widely known The Yellow Kid in McFadden’s Flats (1897) by 60 years.

From an influential point of view, Funnies on Parade (1933) is often considered the first comic book because it was the first published in the now traditional comic book size. And then there is New Fun #1 (1935) by National Allied Publications, later known as DC Comics. It was the first to offer ‘never-before-published’ content; all the others had collated comics previously shared elsewhere.

For a more complete discussion about “What was the first comic book?’, fellow Book Rioter and Comic Book guru Jessica shared her detailed research here.

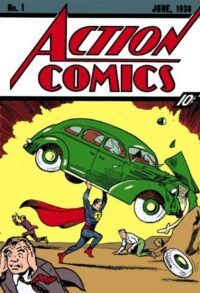

First Comic Book Superhero

Before Superman, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created Dr Occult, a supernatural detective enhanced with superpowers like telekinesis and astral projection. Dr Occult premiered in New Fun Comics #6 (October 1935) with his sidekick Rose Psychic. You might recognise him from “The Trenchcoat Brigade”, so named by fellow member John Constantine in Neil Gaiman’s The Books of Magic. Dr Occult was our first superhero, but he was merely the precursor to our most influential superhero, Superman, first published in Action Comics #1 (1938) by Siegel and Shuster.

Today, it’s near-impossible to get your hands on the original Action Comics #1. You can still read it digitally and see where it all began. However, when we’re talking about the influence of comic books, take a look at The Men Behind Superman by Thomas Campi and Julian Voloj. It is a graphic novel about the back story behind the creation of Superman. Voloj and Campi dive into the friendship between Siegel and Shuster, as well as the micro-culture of the American comic book industry at the time. Of course, Superman was only the beginning. Check out Eileen’s 14 Most Influential Superhero Comics here.

First Female Heroine

Still on the superheroes, the introduction of female heroines made a huge impact on the comic book industry. Our first female superhero with superhuman powers was Fantomah, featured in Jungle Comics #2 (February 1940), created by Fletcher Hanks (as Barclay Flagg). She was followed closely by the first masked and costumed female superhero, The Woman in Red from Thrilling Comics #2 (March 1940), created by Richard E. Hughes and George Mandel.

Both Fantomah and The Woman in Red are seen as the first female heroines, but the real influence on women in comics came from Miss Fury No.1 (1942) by June Tarpé Mills (writing as Tarpé Mills). Miss Fury debuted in newspapers on 6 April 1941, donning a skin-tight black panther skin suit imbued with enhanced strength. She was also the first antihero, resenting the need for a secret identity and not exactly thrilled with her work – but someone has to do it. Despite the violence, the love triangle, and the blatant racism, critics were mostly upset with her ‘revealing outfits’. Her bikini in 1947 scared away 37 newspapers. And this was before Wonder Woman and Phantom Lady!

First Black Superhero

All-Negro Comics, edited by Orrin C. Evans, was created in 1947 and was the first comic book created entirely by Black writers, artists, and editors. It was also the birth of the first Black superhero: Lion-Man, created by George Evans (Orrin’s younger brother). The elder Evans was the first Black American reporter to be on staff at a white-run newspaper. When that business closed, Evans saw an opportunity to move into comics, particularly to improve the characterisation of African Americans in comics. Unfortunately, Evans never had the chance to develop his vision further — the paper company for the first issue refused to sell to him again, and neither would any other paper company. It would be almost 20 years before comic books would feature Black characters in lead heroic roles.

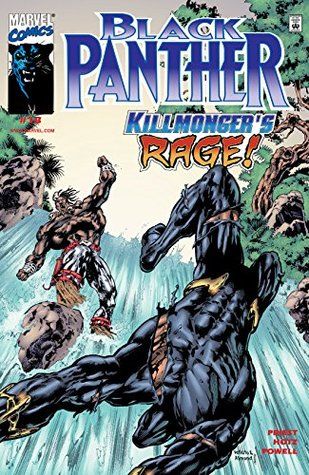

Each of the stories in All-Negro Comics, including that featuring Lion-Man, aspired to portray Black characters with honesty and integrity. Today, we can see that same quality in other Black comic book characters. For example, ‘Killmonger’s Rage’ in Black Panther #18 (1998) by Christopher Priest, Kyle Hotz, and Sal Velluto. It is considered the best of the Black Panther comics, building on Killmonger’s complexities and never shying away from the bigger issues surrounding the character. The story also explores how these same influences could affect T’Challa, showcasing the duality of characterisation. We would never have had the support to publish stories like this if we didn’t have the bravery of All-Negro Comics first.

First Comic to Need a Guidance Code

The uproar of a bikini was only the tip of the iceberg. By the time we hit the 1940s, comic book creators were eager to see how far they could push the boundaries. The straw that broke the camel’s back was “Murder, Morphine, and Me!” in True Crime Comics (No.2) (1948) by Jack Cole. The panel featuring a woman about to have a needle stuck in her eye was a key mention in Dr. Frederik Wertham’s book, Seduction of the Innocent (1954). The uproar achieved by this book led to the creation of the Comics Code Authority. By the time Crime SuspenStories #22 (EC Comics) hit the stands in the 1950s with a cover page depicting a severed head, conservatives throughout the USA were looking for someone to blame.

For more on the Comics Code Authority, Jessica has 10 Things You Might Not Know here.

Underground Comix

In 1954, the Comics Code of Authority embraced its authoritative power and slammed down the hammer of censorship. Conservatives rallied around the United States (and let’s be honest: the majority of the pearl-clutching was in the USA) and were convinced comic books were evil. The Code was created to control both the style and subjects included in any comic book published and sold in the USA.

Creators who refused to bend to the new Code took their work elsewhere, i.e. Underground Comix. Don’t be fooled — just because they were resisting the Code doesn’t mean it was all good. But it did provide a medium to explore storylines and artwork considered too risky for others. The most famous of these was MAD Magazine, founded by Harvey Kurtzman and William (Bill) Gaines from EC Comics. (1952–2018). They avoided the censorship laws by transitioning from comics to zines, however, they originally started out as a series of comics and inspired many artists in the Underground Comix movement.

Fellow Book Riot writer River delved into the history of Underground Comix with amazing detail, and I strongly recommend reading it here.

The First Break From Traditional Panels

Despite the panic seeded by Dr. Wertham, comic book creators continued to influence readers with both their insight and their ability to express it in graphic format. A significant turning point was reached with Impact No.1 (1955) by Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein with art by Bernie Krigstein, colours by Marie Severin, and letters by Jim Wroten.

The story was “Master Race”, the first comic to address the Holocaust; albeit, that’s not the sole reason why it is so influential. How it was depicted in comic book form influenced artists for years to come. Krigstein’s use of repeated panels and broken images captures the depth of panic and fear, giving us the first real indicators of PTSD in comic books. The strength of the story was shown in the breakdowns between each panel of the story, the effect of which had never been considered before. The influence of “Master Race” in both story and art can be seen in the widely acclaimed Maus: A Survivors Tale by Art Spiegelman. Many consider Maus to be one of the most influential comics of all time, but we would never have Maus if we didn’t first have “Master Race” and Impact.

The First Graphic Novel

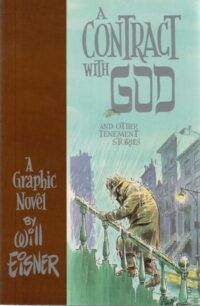

A Contract With God and Other Tenement Stories by Will Eisner

The first ‘Graphic Novel’ may not seem like a big deal in comic books but there is a distinction between the two. A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories by Will Eisner was first published in 1978 and contains four stories centred around the residents of one tenement in the Bronx around the 1930s. It’s grim and semi-autobiographical, balancing between real human experience (including the death of Eisner’s daughter) and his determination to re-examine his own portrayal of race and religion in his previous work.

A Contract with God was also an exploration in how comic book creators could share their stories. No longer were they confined to the set format and layouts of traditional comic books. The idea of graphic novels gave more opportunities to play with expression, layouts, and the relationship between the reader and the printed page.

Comic Books That Influenced Our Reading Lives

The most influential comic books of all time are not always The First. The following are those that have made an impact on our reading lives, even if we don’t really want to revisit them all the time.

Tintin by Hergé

The Tintin books are possibly the most famous of Franco-Belgian comics, showcasing the earliest influence of this particular style on the rest of the world. In Europe, comic books are referred to as bandes dessinées (‘drawn strips’) or BD. Tintin was the most influential of BD, in part because of its popularity and also thanks to the determination of Hergé to flood the market with his books.

There is no denying the problematic nature of Tintin. Racist stereotypes, blatant sexism, a good touch of right-wing fascism — and that’s just the first story, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (Tintin #1). The good news is both character and creator did mature over time. Hergé would later bring a finesse to the ligne-claire tradition of art within Franco-Belgian comics. By the time Tintin was influencing the greater comic book world, Hergé had also developed a stronger narrative using the innocent yet determined nature of Tintin to carry the message of a global community. Since then, Franco-Belgian comics have continued to influence comic book readers around the world. We have seen a flourishing exchange across all markets, in some cases blurring the influences of one culture with another. Some long-standing faves, like Asterix the Gaul by René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo, are great examples of the lasting appeal of Franco-Belgian comics.

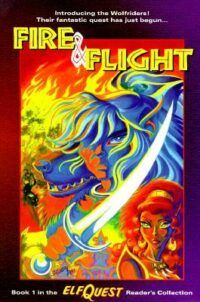

Elfquest by Wendy Pini and Richard Pini

Elfquest is the longest-running independent fantasy graphic novel in the USA. It is also one of the most significant romance comics of modern times, being the precursor for some of our favourite contemporary comics, such as Saga by Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples. And similar to Saga, Elfquest is definitely NOT safe for work/kids/public spaces. Two words: Elf orgies.

Elfquest’s influence went beyond the fantasy and romance genres. The creators, Wendy and Richard Pini were also integral to the growth of independent comics and the importance of printing quality. After their disappointment in the publication of the first issue, the Pinis founded their own company WaRP Graphics, printing Elfquest #2 at magazine-size with glossy full-colour covers and character portrait prints by Wendy Pini on the back cover. Richard Pini took it even further, abandoning the exclusive sales at comic book shops and selling Elfquest through mainstream stores such as Barnes & Noble. These two factors moved Elfquest out of the realm of Underground Comix and into mainstream popularity.

Watchmen by Alan Moore, Art by Dave Gibbons, Colours by John Higgins

Full disclaimer: I do not like Watchmen. However, it is one of the most influential comic books of all time. If you are a fan of Invincible and The Boys, then this is your starting point. This was the moment when someone actually questioned the moral superiority and valour of superheroes. Are they really there to lift up our society and save us from ourselves? Or are they heroes for their own benefit, reluctant in their obligation but doing it anyway because of “benefits”? While it harkens back to the days of Miss Fury, Watchmen‘s balance of detailed art with selective colouring was able to present the story in a far more mature way. Without Watchmen, we wouldn’t have the same courage to question our heroes today.

Tank Girl by Alan Martin and Jamie Hewlett

You don’t have to love it, but you cannot hide from the truth: Tank Girl was a ball-busting disruptor for the comic book industry. It was obscene, it was vulgar, it was the epitome of punk life, and it was everything the rebellious youth of Britain needed in their corner. You can’t have Bitch Planet without a salute to Tank Girl. And Margot Robbie’s outfit in Birds of Prey and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn screams Tank Girl.

Tank Girl’s real power lies in the complete lack of gender dependency in the storytelling. There are story arcs that directly address sexual assault, harassment, and discrimination — and most of the time, they are handled quite well. But more importantly, there is no need for the male presence in Tank Girl’s life. She chooses to have a boyfriend and exercise her own joy of sex. However, both the comic and its later movie adaptation in 1995 were the earliest examples of how to pass the Bechdel Test and create strong female characters who are strong because that’s who they are and NOT because of who they are with.

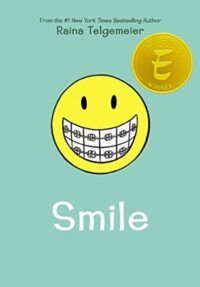

Smile by Raina Telgemeier

Smile is the most contemporary book on this list of influential comic books. Published in 2010, it rode high on the wave of YA novels at a time when many books were focused more on escapism rather than ‘slice of life’. Telgemeier wasn’t the only graphic/YA novel writer out there. She did it so well, she legitimised comics for YA literature. Smile, as a book, takes YA readers seriously. It sits perfectly in that gap between young, ‘easy readers’ and more mature YA storylines. And while it identifies predominantly with girls, the comics that followed were able to push the boundaries between target demographics. Thanks to Smile, comic books like Lumberjanes and The Unstoppable Squirrel Girl were given more attention in the market too.

The Comic Books That Make Us Sit Up and Pay Attention

Wimmen’s Comix (1972) by Various Female Creators

Thank you, Trina Robbins. After co-creating the all-women comic collection called “It Ain’t Me, Babe” in 1970, Robbins was one of the original contributors to Wimmen’s Comix (later renamed Wimmin’s Comix). The Underground Comix scene was heavily male-centric, ironically similar to the mainstream comic book industry. Together with other female artists — including Terry Richards, Aline Kominsky, and Shelby Sampson — Robbins created a safe and supportive space for women to be paid for creating comics. The stories covered a wide range of topics, but most importantly, they shined a light on feminism, sex and politics, the LGBTQI+ community, and mental health. It was the inspiration for many other small-press and self-published comics while also launching the status of female creators.

Wimmin’s Comix paved the way for future creators, like Alison Bechdel and her weekly comic strip, Dykes to Watch Out For. The strip ran in Funny Times from 1983 to 2008, and shared the lives of a diverse group of characters (mostly lesbians). It was the birthplace of the Bechdel Test, and led to her future graphic novels, including Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. For more great comics inspired by Wimmin’s Comix, Laura has 10 Informative & Delightful Queer Nonfiction Comics here. It also includes Bechdel’s latest, The Secret of Superhuman Strength.

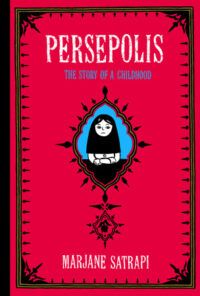

Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi

Persepolis is one of the most banned comics since 2000 for its graphic images and ‘inappropriate’ language. It is also one of the most detailed depictions of the Islamic Revolution in Iran during the 1980s. Satrapi’s story is split into two books featuring a series of BDs: her childhood in Iran during the revolution and her coming-of-age return after living in Austria. There are many autobiographical graphic novels out there; what makes Persepolis stand out is the simplicity of her art and the use of her own story to paint the larger picture of her family and Iran itself. This is not a story of hate or judgement. It is clear Satrapi has a great love for Iran’s rich culture and vibrant people. The influence of this comic is more than the subject material. It is in the way Satrapi has made Iran and the Middle East accessible to a wider audience. Her style of visual literacy has inspired other creators to explore how we can vary the impact of the story through visual cues.

American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang

This is one of those rare books to influence not just the comic book industry but the entire literary world. It won a variety of awards, including the 2006 National Book Award Honor Book for Young People’s literature and the 2007 Eisner Award for Best Graphic Album. Librarians love it. Educators love it. Kids love it. And while it has been questioned for its blatant and rampant stereotyping, that was kinda the point.

American Born Chinese is the weaving of three stories into one, sensitively and yet directly addressing the impact of racial stereotyping on cultural identity and developing multicultural communities. Thanks to the support from librarians and educators, American Born Chinese is frequently held as the best example of literary resources to help struggling students. Something librarians and educators have always known, but it’s great to have an example to influence the future use of comic books and graphic novels in educational environments.

The Rise of Manga

Recently, manga has been rising in popularity in the western world, hitting numbers never before considered possible. We’re talking mainstream popularity, and we’re not sure if it is thanks to streaming services with the accompanying anime or accessibility with webcomics, or even simply a rise in manga coming from outside Japan (primarily China and Korea). The truth is that manga has always had an influence on US comic books (and some Franco-Belgian BD, too).

Astro Boy by Dr Osamu Tezuka

One of the oldest and most famous manga is Astro Boy by Dr. Osamu Tezuka, the ‘Grandfather of Japan’s manga and anime industries’. Tezuka’s vision for the future was the foundation of Astro Boy and was quickly adopted as the turning point for manga and its First Wave Resurgence post-World War II. The iconic work featured towering skyscrapers, flying cars, and robots in every home, but most of all, Tezuka included children in every day life, ensuring they could always see themselves in this future life. Bonus point: ‘Seeing’ themselves was key to Astro Boy’s design. Big eyes were Astro Boy’s dominant feature. To this day, younger characters in anime and manga often have the biggest and most adorable eyes.

For more about Astro Boy and Tezuka, check out our story on the 70th anniversary here.

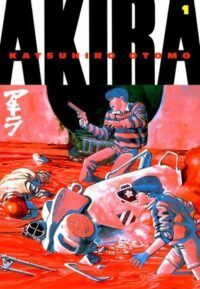

Akira by Katsuhiro Otomo, Translated by Yoko Umezawa, Linda M. York, and Jo Duffy

In the world of manga, there is pre-Akira and post-Akira. It was the anime that smashed its way into the US market and brokered a whole new audience for manga around the world. With punk-ass Tokyo, gang warfare, and the coolest motorcycle scenes ever illustrated, Akira was the birth of Cyberpunk. Again, others dabbled in this sub-genre pre-Akira, but nothing was ever quite the same afterwards. Akira set the benchmark. Cowboy Bebop, The Matrix, and Ghost in the Shell: all of these were influenced by Akira.

Sailor Moon by Naoko Takeuchi

Before Sailor Moon, manga was clearly marketed by the target demographic: shōjo (young females), shōnen (young males), seinen, etc. Sailor Moon broke that rule and ran heavily with it into the future. Originally, Takeuchi started with Codename: Sailor V, a manga serial first published in 1991. When the series was proposed for anime, Takeuchi redeveloped the story to make Sailor Venus part of a team of magical girls.

Sailor Moon was not the first to do it; you can read more about the history of ‘magical girls’ here. What it did do is mix the ‘magical girls’ genre with tropes usually found in shōnen anime and manga, making Sailor Moon super-appealing to ALL demographics. Future manga and comics were quick to realise they didn’t need to cater to only one demographic anymore.

Changing How We Write Comics

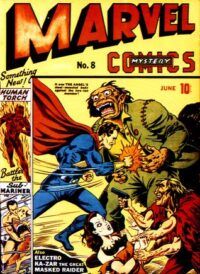

Marvel Mystery Comics No. 8 (1940) by Carl Burgos, Bill Everett, Joe Simon (Editor) and Alex Schomberg (Cover Artist)

Whether you love a good crossover or hate them with the passion of a thousand suns, we can officially blame Marvel Comics. The first ever superhero crossover pitted The Human Torch against Namor, forcing readers everywhere to spend more money on back issues and cross-referencing. And this was WAY before the internet. This comic was probably more of an influence on the marketing-and-accounts department than the readership, but it still counts in the grand scheme of things.

The Flash #123 (1961) by Gardner F. Fox, Art by Carmine Infantino

Every time you question the continuity of a comic book story, it’s a salute to The Flash. The scene is where Barry Allen (The Flash Silver Age) meets Jay Garrick (The Flash Golden Age). Barry mentions he had originally thought to call himself The Flash because he recalled reading comics about Jay’s adventures when he was a kid.

The Amazing Spider-Man #121 (1973) by Gerry Conway & Gil Kane

There’s a reason comic book readers have trust issues, and that reason is Gwen Stacey. It was the first time a major character was killed off. The superhero did not save the girl. And she stayed dead (well, at least for the longest time). You relied on Spider-Man’s confidence, his skill, and his abilities. And you trusted the belief that Marvel — nay — any comic book would never go that far. Yeah, well, they did. And every now and then, some other creator thinks it’s okay to do it too (e.g. Tom Taylor killing off Lois Lane in Injustice or the gimmicky vote to save or kill off Jason Todd in Batman #427).

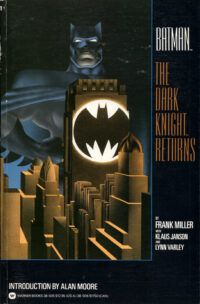

The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley

The Dark Knight Returns has long been held by many critics as being the gold standard to which all Batman stories will be forever compared. Miller’s goal was to shake up the superhero genre, completely revising one of the most iconic characters in comic book history and forcing readers to question everything.

Where to start? Okay: we have an aged Caped Crusader who really does want to retire. Wayne is clearly identifying as a trauma victim, opening the gates to far more psychological analysis than in previous storylines. The story itself was set outside the established DC continuity, giving Miller a bit more room to play with both heroes and villains.

With almost 200 years of history and an ever-growing range of genres, comic books have spread their influence over every genre of literature (and created some of their own). While this list shares 23 of the most influential comic books of all time, it is nowhere near comprehensive. What’s on top of your list?